The Archaeology of Legacy Code: Reading Systems Like Texts

Working with legacy code is archaeology. You're excavating a site where the civilization has moved on, sifting through artifacts left by people you'll never meet, trying to reconstruct why they built what they built.

The hardest part isn't the code itself. It's that the whole context, the people, the culture, the constraints that created this system, isn't around anymore. You can't interview the original inhabitants. You have to read their structures like texts and infer what they were thinking.

Why Archaeology Is the Right Metaphor

Ward Cunningham suggested viewing code in 2-point font to get an overall feel for a program's structure. I get what he's after. You're trying to see the shape of the thing before you get lost in the details.

But as a consultant, you rarely get a long runway for that kind of holistic understanding. You're expected to add value now, not six months from now after you've achieved enlightenment about the system architecture. And that's exactly why the archaeology metaphor fits.

Archaeologists don't have the luxury of complete knowledge either. They work with fragments. They balance the desire to understand everything against the practical need to produce findings. They develop techniques for reading partial evidence and making informed interpretations.

That's the job with legacy code. You're reverse engineering intentions from artifacts.

Reading the Layers

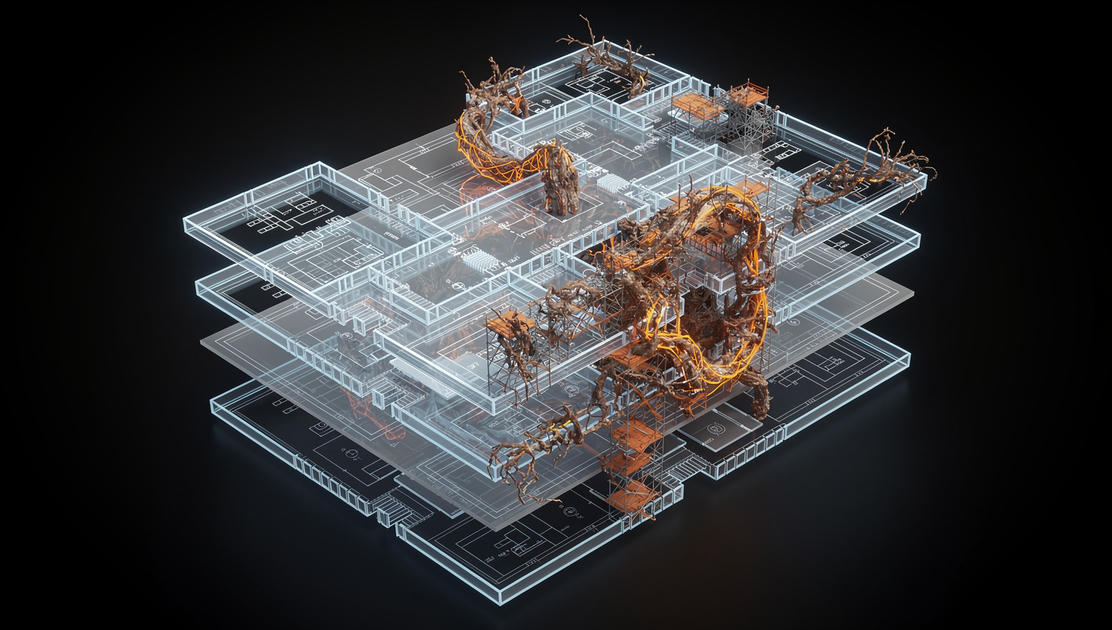

Someone described legacy systems as having three archaeological layers: the intentional architecture, the evolutionary additions, and the emergency fixes that became permanent. This framework maps perfectly to what I actually see.

The intentional architecture is like the original foundation of an old house. If it was well planned, you can feel the consistency. There's a straightforward, similar pattern throughout. Someone thought about this before they built it.

The evolutionary additions are where someone took that original pattern and grew it into something similar but not the same. The DNA is there, but it mutated. Like a house addition that tries to match the original style but uses different materials, different proportions. You can tell it came later.

The emergency fixes look like what they are. Band-aids slapped on top of whatever structure existed. No pretense of fitting in. Someone had a deadline or a crisis and did whatever would make the immediate problem go away.

You learn to recognize which layer you're in by the structure and organization. Original code has rhythm. Evolutionary code has echoes of that rhythm. Emergency code has no rhythm at all.

The Primary Source Material

The most useful technique I've developed for reading unfamiliar systems isn't technical. I try to understand the people and personalities and story behind the code. Not only the people who wrote it, but the people using it.

How users interact with software tells you why certain decisions were made. Code doesn't write itself. Someone sat down and made choices based on what they understood about the problem, the users, the constraints they were working under.

Venice is built on wooden stilts driven into the hard ground beneath the lagoon. When that foundation works, nobody calls for outside help. I get called when half the city starts collapsing underwater.

So I'm rarely discovering buried treasure. The elegant, well-designed systems don't generate distress calls. What I'm excavating is shortcuts and workarounds. Things that kind of work by accident. Features built on assumptions that stopped being true years ago.

Reading with Grace

Here's something important about archaeological interpretation: you have to account for the technology and knowledge available to the original builders.

We live in a time where information is incredibly accessible. You can find five good ways to do something in minutes. I had a headlight bulb go out recently. The auto parts store couldn't figure out how to install the replacement and suggested I take it to a mechanic. I went home, watched a five-minute YouTube video, and did it myself with hand pressure. No tools needed. Five options for tutorials, and any of them would have worked.

Ten years ago, fifteen years ago, twenty years ago, when a lot of legacy code was written, developers didn't have that access. They couldn't search for solutions to every problem. Stack Overflow didn't exist for much of this code's lifetime. AI wasn't generating code. They were working with the patterns they understood and the resources they could find.

Most of them were acting in good faith, doing the best they could. When all you have is a hammer, everything looks like a nail. I see that constantly in old code. Maybe a lack of curiosity about whether there was a better tool. But that's different from malice or incompetence.

Reading legacy code well means extending that grace while still being clear-eyed about what needs to change.

Conversations Across Time

I often feel like I'm having a conversation with long-gone developers through their code. It's more like arguments with them, honestly. You can see what they were going for. You can see the decisions they made given their culture, their proficiency level, the practices of the time.

There's a project I came into after the main developer abruptly left. Guru type who'd built multiple applications himself, getting everything done solo. But tech debt caught up with him. Every change cascaded throughout multiple systems. They tried to bring in another developer who didn't have the right skillset for a small team.

I was brought in to help him. He exited the company two weeks after I showed up. Barely any transition. Said everything was documented. I tried to contact him a few times with questions. "Yeah, I don't know."

So you reverse engineer intentions from the artifacts. There's a saying about not tearing down fences you find because you don't know why they're there. Or the turtle on a fence post: you may not understand why it's up there, but it didn't get there on its own. Someone put it there with intention.

Two and a half years later, we're still working with that client. Still discovering areas of code where someone didn't think through the consequences. Packages selected that were barely tested, not many maintainers, now dead projects. But they're pervasive throughout the codebase. Artifacts of decisions made under conditions we can only partially reconstruct.

The Time-Blindness Pattern

The biggest pattern I find when excavating legacy systems is what I call time-blindness. Doc Brown would say they weren't thinking fourth dimensionally. Developers write code expecting it to be used for a few years. Twenty-five years later, it's still running, used in ways nobody anticipated.

There's a company I contracted for where most of the system was written by engineers who weren't software developers. They were making things happen. The database wasn't designed. Tables treated like Excel sheets.

Their thought process: I want a tool that works now. Once it works, we can prove value and get budget to hire someone to build it properly.

But management sees a working tool and asks why they need to hire someone if it's already working. The amateur developer can't articulate what's wrong. So nothing changes.

My friend got called in fifteen years later. Legitimate software architect, really sharp. He had to unwind two decades of make-it-work changes, none made by someone who understood the long-term implications. Impossible to completely unravel. But now they wanted AI and ML on their data, and the data was garbage. Different schemas mashed together. Dangling reference data from pivots that never got cleaned up.

They asked why they couldn't get anything done. They had twenty-five years of tech debt and were asking one guy to pay it down in a year while simultaneously building new features.

Then the defensiveness: we did the best we could, this system worked for us for a long time.

That's true. But it's not an answer to why everything is breaking now.

What the Excavation Teaches

Reading legacy code changes how you write new code. The main lesson: clarity above all.

I see developers trying to be clever all the time. Custom password hashing algorithms with constant-time comparisons to prevent timing attacks. This problem has been solved in many ways. Every language has libraries for it.

There was a project where a colleague wrote a Kafka stream reader from scratch. Very complex. I tried to have a conversation about it. Other people have figured out how to read from Kafka streams. We should manage code specific to our project, not reinvent generic infrastructure.

You're never going to write something as thorough and well-tested as a library where that functionality is the whole point, not a means to an end. Someone else has multiple people's eyes on it, extensive testing, continuous maintenance.

I thought we had a meeting of the minds. Then later, in front of the whole team, pushback about the decision. That code got abandoned eventually. But the interaction stayed with me.

The Right Layer of Abstraction

Getting logic in the right layer matters more than I understood before I started excavating other people's systems. When you get it wrong, you're mixing data fetching and data transformation and business logic together. It makes things difficult to test. Difficult to reason about.

When you're working on something, you want to think about one thing at a time. Our working memory is small. We can't manage all levels of complexity simultaneously.

If I'm an engineer driving a train, trying to get somewhere on time, I don't want to think about how the timepiece mechanism works. I don't want to worry about whether it's giving me the right time right now. I want to look at the watch, see the time, know how fast to go.

When abstraction layers are improperly mixed, you're worried about something that should be an input to your current process. You're handling situations where that input might be influenced by things happening outside what you're looking at. It becomes combinatorial explosion.

How do you recognize you're in the wrong layer? When you're thinking about things you shouldn't need to think about at your current level of abstraction. That's the signal.

Writing for Future Archaeologists

The discipline I've adopted from excavating other people's systems: don't solve problems that other people are solving. Don't be clever. Don't create complexity that's unnecessary.

Clarity. Simplicity. The right logic in the right layer. Making things easy to follow.

Every time I'm tempted to write something clever, I think about the person who'll be reading my code years from now. They'll be trying to understand why I made the decisions I made. They won't be able to reach me for answers. They'll be reading my code like a text, trying to infer intentions from artifacts.

I try to leave them a system they can read.